The Magazine “Junge Kirche”

Church newspaper and magazine publishing became took on great importance for the oppositional Confessing Church in the Nazi era. The “coordinated” secular press was no longer reliable because it reported entirely in the spirit of the German Christians. The secular media controlled by the Nazis very soon suppressed reports on the struggles between the camps inside the Protestant church entirely. Hence, the church’s own magazines played a crucial role in communication and the exchange of information within church opposition.

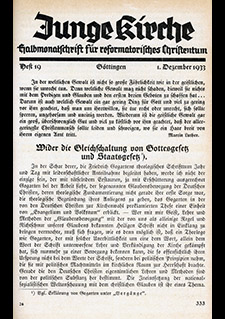

The magazine “Junge Kirche” was exceptionally important. It had been founded by the Young Reformation movement in just 1933 and appeared as the “Halbmonatsschrift für reformatorisches Christentum” starting in the fall of 1933. The magazine had been founded with dual intentions: On the one hand, it was intended to be a forum for opinions within the Confessing Church. A broad range of authors from the emergent church opposition had their say in it. At the same time, it included a section with detailed information on all of church life in Germany, which furnished readers some bearings in the ecclesio-political turmoil of those years.

Its editor Hanns Lilje and the editorial staff were located in Berlin. The magazine was printed by the academic publisher Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht in Göttingen. The magazine met the need for information in that day. The number of direct subscribers rose to over 30,000 in 1934. It was not sold in bookstores since no one was willing to distribute a magazine considered to be politically undesirable press because of the government reprisals to be expected.

The church press’s work was subject to the strictest censorship rules. In particular, the “Frick Decree” of November 1934 from the Reich Ministry of the Interior hit the Protestant press hard. It flatly forbade the publication of anything that dealt with the Protestant church, with the exception of official announcements from the Reich Church government.

The editorial staff of the “Junge Kirche” had to employ cleverly devised, occasionally semi-legal strategies of circumvention in order to continue working as accustomed. A “Verlag Junge Kirche” was founded in 1933 to protect the publishing house from the state’s clutches. In actuality, it was intimately interconnected with the publisher Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht with which it shared offices.

The strategically important news section was especially affected by the “Frick Decree”. The editorial staff developed a special system of citation to circumvent it: it no longer reproduced laws, decrees, announcements, bans, excerpts from speeches and statements from the Confessing Church as original news, but quoted from official law and ordinance gazettes, the Nazi press or German Christian outlets instead, citing the source exactly. Authorities had difficulty censoring this “press roundup, which briefed readers of the “Junge Kirche” on the church’s current situation.

Very early on, the editorial team resorted to treating controversial issues in theological jargon whenever possible. This gave outsiders a harmless impression in order to provide the censors few targets. A specially developed coded language was used for communication between the editorial staff in Berlin and the publisher in Göttingen to circumvent telephone surveillance.

The publisher had a “mole” in Gestapo headquarters in Hannover, who occasionally warned management before the censors struck by anonymously phoning in the tip that Hawkeye is coming. The church press and the “Junge Kirche” in particular thus took on an important role in the development of church opposition. Its focus was on preserving the Protestant church’s political independence. In keeping with its conception of itself, the magazine did not want to turn into an outlet of political opposition.

Pressure on the editorial staff of the “Junge Kirche” to conform increased steadily, especially after the Nazi government changed its church policy in 1935. The balancing act between conformity and self-assertion grew more and more challenging. Government regulations had become so drastic by 1938 that the still remaining independent church press no longer had any latitude to report independently. The Reich Chamber of the Press eventually ordered the discontinuation of all religiously motivated magazines in the summer of 1941 on account of the war.

Source / title

- ©Evangelische Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Kirchliche Zeitgeschichte, München