Oppositional Alternatives in the Church Election

The church elections suddenly announced by the Nazi state for July 23, 1933 were intended to clarify the ecclesio-political balance of power within the Protestant church. The church parties taking part only had a total of nine days to present themselves and their ecclesio-political objectives to the general public.

The German Christian Faith Movement had been experiencing a large influx of members for months. In addition, it was consistently supported by local NSDAP agencies, Party press and propaganda. It did not need a long period of preparation and profited from the short time allotted for the election campaign.

Things were different for the Young Reformation movement, the group of Protestant pastors and theologians who combatted the German Christians’ ecclesio-political objectives. They felt challenged by the scheduled church election and took up the fight despite the short time for preparation that put them at a disadvantage.

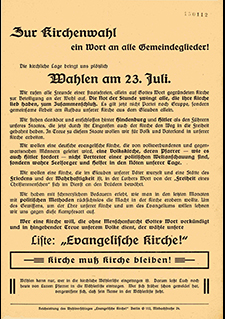

Hanns Lilje, Walter Künneth and Martin Niemöller started a campaign initiative with modest means virtually overnight. In very short time, the leadership of the Young Reformation managed to unite all of the Protestant forces and groups as the “Evangelische Kirche!” nominees, which did not sympathize with the German Christians. In Berlin, the list of candidates set up a campaign office whence publicity materials such as flyers with “announcements” and “appeals” for the upcoming election were sent out to parishes throughout Germany.

The German Christians’ publicly touted extreme closeness to the Nazi state and the support they enjoyed from NSDAP put pressure on the “Evangelische Kirche!” to likewise declare its loyalty to the state so as not to appear to be an alternative list of candidates disloyal to the state. The leadership of the Young Reformation movement therefore strove in public campaign statements always to stress its loyalty to the state and its highest representatives.

What is more, they emphatically stressed their pursuit of a church free of representatives with any political ideology. They unambiguously asserted that political methods had no place in the church since the church is apolitical by nature as was expressed in the campaign slogan church must remain church.

The declaration of loyalty to the “new” state and the plea for a free, depoliticized church were one outcome of the theological conceptions of order as well as the mounting public pressure to legitimize itself during the election campaign. In the end, the entry of the “Evangelische Kirche!” list of candidates proved to be ambivalent: They proved their clear opposition to the German Christians, especially rejecting their symbiotic closeness to the Nazi state. On the other hand, the affirmative conception of the state also expressed by the “Evangelische Kirche!” list signified the abandonment of a fundamental element of Christian liberty because this course left the state more and more to itself in its deeds without the church fulfilling its “role as a guardian”.

Given the heavy-handed support for this church party, the German Christians’ substantial win was an expected outcome of the church election. Although the outcome was disappointing for the Young Reformation movement and its list, as the church struggle progressed, the Young Reformation movement’s involvement in the election took on significance for the development of the Confessing Church later.

Source / title

- ©Evangelische Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Kirchliche Zeitgeschichte, A 1.4