The Altona Confession

Hans Asmussen started his new job as senior pastor of Christian’s Church in Altona in May of 1932. Not incorporated in Hamburg until 1936, the port town on the Elbe in Holstein was a stronghold of the labor movement. On Sunday, July 17, 7000 Storm Troopers marched through “Red Altona” and fought bloody brawls with members of the SPD and KPD.

As Asmussen was preaching on the Fifth Commandment, a gunfight began, which left numerous dead and wounded. “Altona’s Bloody Sunday” shocked the community. The pastors of the provostship held an “emergency worship service” on July 21, which called to repentance by Bible readings and hymn singing. A sermon was dispensed with because the church wanted to listen entirely to God’s Word rather than allowing itself to be used for political clashes.

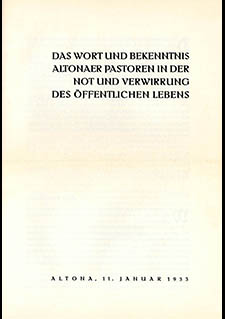

The “Wort und Bekenntnis Altonaer Pastoren in der Not und Verwirrung des öffentlichen Lebens” (Message and Confession of the Pastors in Altona in These Perilous and Bewildering Times in Public Life) or “Altona Confession” for short, which the pastors developed in the following months under Asmussen’s influential guidance, was also along the same lines: The church cannot and does not want to enter any alliance in the political struggle. Instead, it must concentrate on its core mission of sharpening consciences and preaching the Gospel. It should thus be made immune to misuse by any political movement.

In its five articles, the “Altona Confession” already indicated what would later characterize the Confessing Church as such: Rather than fundamentally opposing National Socialism political from the outset, it intended to strengthen the church’s mission to teach, preach and minister confidently on the foundation of the Bible and Confessions alone.

Precisely this made the text a political provocation, however, because it challenged National Socialism’s and Communism’s claims to totality and severely bound them with the fundamental authority of God’s Word.

The Confession was published on January 11, 1933, shortly before Hitler’s assumption of power. At the same time, Asmussen fully annotated it in his book “Politik und Christentum” (Politics and Christianity), also published in 1933.

Asmussen was sent into retirement virtually on the day of the Confession’s anniversary; other colleagues experienced much the same. His certificate of retirement mentioned that his conduct constituted an ongoing protest and willful resistance against the [...] church government as well as a conflict with the German Evangelical Church.

Source / title

- © Ev. Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Kirchliche Zeitgeschichte, München KK B 350-7