Solidarity Denied

Two days before the boycott of Jewish businesses on April 1, 1933, which had been organized by the Nazis, the “Reich Representation of German Jews” turned to the leadership of the Protestant church (as well as the president of the German Catholic Bishops Conference) seeking help. They were hoping for a word of solidarity, also in the interest of freedom of religion in general.

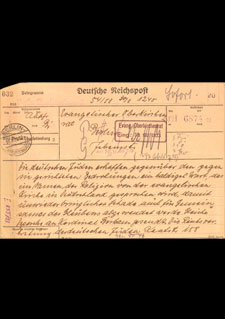

In a letter of March 24, 1933, the Federal Council of the Churches of Christ in America had suggested publishing a statement together with the German Evangelical Church Federation declaring anti-Semitism to be unchristian. The requested statement of solidarity never materialized. On the contrary, the church government actually felt compelled to issue a warning about atrocity propaganda from abroad.

It probably did so out of a mixture of repression, mollification, downplaying and latent hostility of its own toward Jews. Not only centuries-old traditions of religious anti-Judaism but also the anti-Semitic theses of the influential court chaplain Adolf Stoecker (1835–1909) continued to exert influence. His hostility toward Jews was primarily economically and culturally motivated.

Stoecker’s remark that, while he actually had nothing against the Jews in Jerusalem, he indeed had something against those on Jerusalemer Strasse, a business district in Berlin, was much quoted in church circles. Stoecker’s anti-Judaism and his anti-Semitic theses had deeply influenced the upcoming generation of theologians well into in the Nazi era.

Source / title

- ©Evangelisches Zentralarchiv in Berlin, Best. 7 Nr. 3688