“Paula” at Pentecost in Köngen

During World War II, the parsonage in Köngen was not only a place of refuge for hunted Jews but also an annual meeting place of the Protestant Girls Association from the immediate vicinity and surrounding areas. Retreats and larger gatherings of the Protestant Youth in Württemberg, especially major events, had been prohibited once and for all when the war broke out.

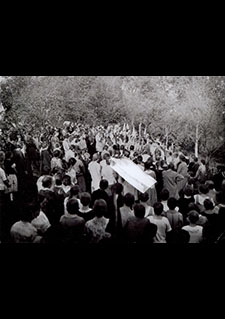

In order to circumvent this prohibition, the Stöfflers, in consultation with Württemberg regional youth pastor Dr. Manfred Müller, came up with ostensibly personal “parsonage invitations” to Köngen, called “Paula” by the young people. On each Pentecost Monday from 1940 to 1944, initially 500 and finally around 1500 girls walked or rode bikes to the gathering of young Christians in Köngen.

in his memoirs “Jugend in der Zerreissprobe” Pastor Manfred Müller wrote:

Shortly before Pentecost of 1940, Pastor Stöffler in Köngen called me up and said, “Imagine, our parish collected (as I remember) 538 g of silver for a new communion set. Isn’t that fabulous?” I confirmed this and thus knew that this number of girls had registered. From year to year, it became more. In 1944, that is, in the last year of the war, 1500 sat in the church, which was filled to the brim.

In the first years, many still arrived by train. In the last year, this was expressly forbidden “because of the large numbers traveling”. So they simply rode bikes or walked. Some got up at four o’clock in order to arrive at nine o’clock. Girls, who directed them to places to park their bikes, were posted at the outskirts of town for the cyclists. Despite their great number, not one ever got mixed up or let alone stolen!

The special thing about the gatherings in Köngen – apart from their size – was the two bowls of noodle soup in the parsonage for every attendee! Pastor Stöffler’s family had cleared out the entire living floor and even brought the beds to the loft. Tables and chairs were put in their place so that 200 girls apiece could eat at the same time, on white tablecloths, for it was a special day of course!

They began cooking in borrowed, large sausage pots early in the morning. The family had been saving the food – meat, eggs and noodles – since the beginning of the year or it had been donated by the congregation. In the last year, two Gestapo agents appeared precisely at the moment a girl was bringing twenty eggs into the house. Naturally, that was not allowed. Yet, what could they say when the pastor told them that the eggs were thanks for a bridal bouquet one of his daughters had arranged from the garden on Saturday for the bearer’s sister.

At lunch, feeding 200 girls each time and setting the tables for the next took half an hour. Plates and silverware were largely borrowed from the village’s restaurants and made identifiable by the parsonage with sealing wax marks on the bottom of plates. One of the restaurateurs even gave twenty-four heavy silver spoons. When they were brought back to him by the pastor’s wife, he simply threw them in the drawer rather than even count them. He was sure that the number was correct!

The two chief dangers were the air raid warnings and the Gestapo. The sounding of the air raid warning only after conclusion of the final meeting, when everyone was already out of the church had been a special gift. Naturally, the two Gestapo men on surveillance were conspicuous among so many girls. They took notes assiduously but never took any action.

And the day’s program? Apart from the group eating in the parsonage at the moment, we remained in the church the entire day. We began with a worship service. Brief singing – chiefly canons, which had their heyday at that time, as well as folksongs – was followed by a one-hour Bible study. The attention was amazing and undivided.

Then we sang again, I myself directed from the pulpit, the parish pastor told stories from the diaspora, often with slides – or showed pictures of Christian art. The conclusion was always a Christian woman’s biography, which Mrs. Stöffler – speaking from the pulpit – recounted so enthrallingly that it left a deep impression (Manfred Müller: Jugend in der Zerreissprobe. Persönliche Erinnerungen und Dokumente eines Jugendpfarrers im Dritten Reich, Stuttgart 1982, p. 83–85).

Source / title

- © Photo: Ruth Stöffler