Friedrich Hofmann: Against Ostracism of Jews

Pastor Friedrich Hofmann (1904–1965), chaplain of the Munich Inner Mission since October 1, 1931, was an important helper to the disadvantaged and disenfranchised during the Nazi regime.

Hofmann came from a family of teachers in Untersiemau near Coburg. His origins imbued him with a nationalistic, liberal and moderately Lutheran identity. Under the influence of his family, he participated in church life at an early age and pursued musical and artistic interests. After earning his degree in theology and training at the theological seminary in Nuremberg, he became the municipal vicar in Würzburg in 1928 before he was appointed director of the Munich Inner Mission in 1931 at the initiative of Hans Meiser (1881-1956), then-member of the high consistory and his mentor.

Like most of the members of his generation, Hofmann endured the loss of the World War I and the collapse of Imperial Germany. In May of 1933, he joined the NSDAP but hardly took part in party life. He primarily hoped for an improvement of living conditions for the socially disadvantaged by the National Socialists. He additionally trusted in Hitler’s ecclesio-political promises.

After approving of the Nazi state at first, his hopes were increasingly dashed. He remained a member of the party, however, in order to protect the Inner Mission’s social welfare agencies from the clutches of the National Socialist People’s Welfare and to be better able to influence party and state authorities.

The Nazis’ increasingly open anti-church and anti-Christian policies and neopaganism’s advances contributed to Hofmann’s disillusionment. He backed the Confessing Church and resolutely sided with Regional Bishop Hans Meiser in the Bavarian Kirchenkampf.

During the further course of Nazi regime, he opposed the Nazis’ anti-Christian weltanschauung in lectures, distributed forbidden pamphlets in parishes, did not allow party officials to speak at the Inner Mission’s facilities, converted “staff roll calls” required by the Nazi state into devotions and refrained from using the “Nazi salute” in official correspondence within the church.

Hofmann’s conscience came into conflict no less with the Nazis’ inhumane treatment of the disadvantaged in society – for whom Hofmann was responsible by virtue of his post as director of the Munich Inner Mission – and of people regarded as Jews according to the criteria of Nazi racial ideology.

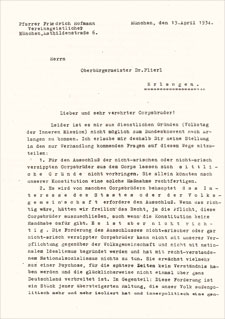

A letter of Hofmann’s of April 13, 1934 to his Corps brothers and Erlangen mayor Hans Flierl (1885–1974) dating from the phase of his disillusionment. While standing by National Socialism, Hofmann exceptionally clearly and perspicaciously declared his opposition to the demand to expel “non-Aryans” from his student fraternity, the Corps Bavaria, at the university in Erlangen.

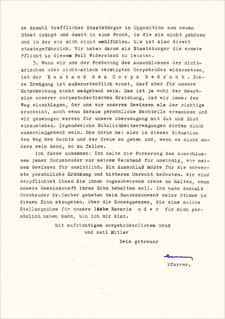

In his letter, Hofmann argued that the demand to expel “non-Aryans” was neither morally nor politically justified. Instead, it was the manifestation of a psychosis, for which future generations would not have any understanding: I consider the demand to expel those Corps brothers to be senseless before my reason, to be immoral before my conscience. For them, expulsion would amount to the gravest personal offence and bitter injustice. Hofmann additionally expressed his willingness to bear the consequences of his decision of conscience both for himself personally and for the corps, the continued existence of which was in jeopardy were the “non-Aryans” to remain.

When he wrote his letter, Hofmann was evidently not yet aware that his stance was fundamentally irreconcilable with National Socialism. He later considered the NSDAP to be a criminal organization. He did more than just support the cause of “non-Aryan” Corps brothers: In addition to rendering aid to the disadvantaged and disenfranchised in his posts at the Inner Mission, the church government entrusted him with the task of caring for “non-Aryan” Christians in 1938. He was additionally already in charge of chaplaincy in Dachau concentration camp in 1934 and for inmates sentenced to death in Munich’s Stadelheim prison as of 1939.

After World War II, he had to relinquish his office as chaplain because of his party membership and took on a job as a parish pastor before becoming the military chief of chaplains in Bonn in 1957 at the recommendation of Heinrich Grüber (1891-1975).

Source / title

- © Private collection of Helmuth Hofmann, Ahorn-Finkenau