Church Government: Work in the Confessing Church

The German Christians’ desire not only to coordinate the Protestant church with the Nazi state organizationally but also to adopt Nazi ideology and forsake fundamental tenets of Christian faith in the process became clear in the fall of 1933.

General protest arose in the church when the German Christians introduced the Aryan paragraph in the Reich Church and the regional churches they controlled and thus made church membership contingent on the Nazi principle of race. Opposition against the German Christians’ heretical doctrines and the German Christian church governments in the Reich Church and regional churches formed within the church in the Pastors’ Emergency League under Pastor Martin Niemöller (1882–1984) in September of 1933.

Bavarian Regional Bishop Hans Meiser (1881–1956) also sided with the opposition within the church. He resolutely spoke out against the German Christians’ heresies, the Reich Church government’s breaches of the law under Reich Bishop Ludwig Müller (1883–1945) and the disciplining of the pastors of the Emergency League. He very soon became the spokesman of the church leaders who were not German Christians, most notably Württemberg Regional Bishop Theophil Wurm (1868–1953) and Hannover Regional Bishop August Marahrens (1875–1950).

Differences in the opposition within the church became evident very early, though: While the Lutheran bishops Meiser, Wurm and Marahrens feared for the purity of the Reformation confessions and wanted to assure the survival of the people’s church, the pastors of the Emergency League under Niemöller gave priority to bearing witness to Christ there and then.

A rift between the bishops and the Pastors’ Emergency League already occurred in January of 1934 when, under strong pressure from Hitler, church leaders once again subordinated themselves to the heretical Reich Bishop. Meiser realized his error soon afterward, though. In the ensuing months, the Bavarian regional church then played a significant role in uniting the opposition within the church into the Confessing Church.

Meiser and Wurm obtained an audience with Hitler in March of 1934 but he rejected the church opposition’s demands. Meiser’s statement that, under these circumstances, the bishops would simply become the Führer’s most loyal opposition became famous. Hitler responded by flying into a fit of rage and calling the bishops traitors to the nation, enemies of the Fatherland and destroyers of Germany (H. Schmid, Wetterleuchten, 62).

At Meiser’s initiative, the churches in Southern Germany and the oppositional groups in Westphalia formed an action group, which soon included the oppositional forces from all of the regional churches. When the opposition within the church united in the Confessional Fellowship of the German Evangelical Church at the Confessional Day in Ulm in April of 1934, Meiser read aloud the communiqué in which the Confessional Fellowship declared itself to be the sole legitimate church.

Many Bavarians attended the first National Synod of the Confessing Church in Barmen in May of 1934, at which the Confessing Church was constituted and the Theological Declaration of Barmen was adopted. The entire Confessing Church of Germany showed its solidarity with the Bavarian regional church when it was supposed to be forcibly incorporated in the Reich Church in October of 1934 and the second National Synod of the Confessing Church was convened in Berlin-Dahlem.

The differences within the Confessing Church had already manifested themselves once again in conjunction with the first two National Synods of the Confessing Church. While Bavaria gave its support to the Theological Declaration of Barmen, the denominationally strongly Lutheran church government kept its distance.

One member of the Bavarian delegation, Hermann Sasse (1895–1976), a theology professor at the university in Erlangen, even departed prematurely from Barmen because he considered the declaration to be a violation of the evangelical Lutheran conscience (quoted from C. Nicolaisen, Herrschaft, 309). The church government’s reserved stance was motivated by the fear that the declaration could be seen as a confession that established a new “confessing” church that would be unify Lutheran, Reformed and United Christians without any distinction.

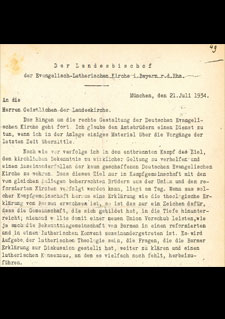

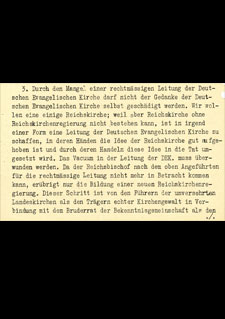

Regional bishop Meiser’s circular of July 21, 1934 to the Bavarian clergy in which he spoke of an action group with brethren from the Union and in the Reformed churches dominated by the same concern was characteristic for the church government’s point of view. Although he judged the Declaration of Barmen to be an indication that the fellowship, which had formed, extended down into the depths, he simultaneously stressed that nobody intended to promote a new Union with this and announced that it would first be Lutheran theology’s task to clarify the questions further, which the Declaration of Barmen had posed for discussion and to reach a Lutheran consensus.

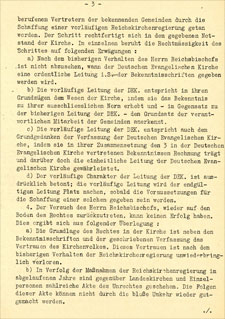

The Bavarian church government did not consistently give its support to the resolutions of the National Synod of the Confessing Church in Berlin-Dahlem, either. Emergency church law was declared at this synod and a resolution was passed to form Confessing Church organs of the church government. The Reich Church was supposed to be run in the future by a council elected from the National Council of Brethren.

In November of 1934, the bishops Marahrens, Meiser and Wurm reached an agreement with the National Council of Brethren to form a “Provisional Church Government” presided over by Hannover Regional Bishop Marahrens. A member of the Bavarian high consistory, Thomas Breit (1880–1966), was also a member of this church government. As a result, Niemöller and a few others resigned from the National Council of Brethren for a short time.

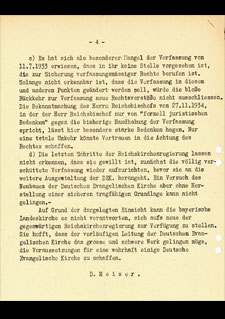

The disputes over the formation of the First Provisional Church Government (VKL) were sparked by, among others, the figure of President Marahrens, whom the circles around Niemöller rejected as too conciliatory. Above all, however, there was disunity about the path by which the common goal of a confessional Reich church government was to be reached: Whereas the members of the “radical” Confessing Church wanted to achieve this goal at any cost, even if it meant the loss of the state-recognized people’s church, the “moderate” forces around the Lutheran bishops Marahrens, Meiser and Wurm were intent on attaining maximum conformity with the existing Reich Church constitution and recognition by the state.

In a letter of December 11, 1934 explaining the reason for the formation of the Provisional Church Government to the clergy, the regional consistory made no mention of the differences that had arisen in the Confessing Church. In addition to its loyalty to the confession, the regional consistory especially stressed the Provisional Church Government’s closeness to the existing Reich Church constitution and its provisional nature until the appointment of a constitutional government.

The Bavarian church government’s relationship with the Confessing Church remained shaky until the end of the Nazi regime: It was willing to participate in an action group against the German Christians and the Nazi state’s anti-church measures but unwilling to allow full communion with Reformed and United Christians. It was willing to participate in joint bodies, but only provided this did not mean losing state recognition from the outset and thus options for action in a people’s church.

Source / title

- © 1+2: Evangelische Arbeistgemeinschaft für Kirchliche Zeitgeschichte München, A 30.1