Walter Hildmann: Against Dying in War

Walter Hildmann (1910–1940) was of the few Bavarian clergymen who ventured to criticize the conditions in the Nazi state publicly. He came from a pastor’s family in the Unterallgäu. During his last years of school in Kempten, he became friends with Helmut Gollwitzer (1908–1993) who became an exponent of the Old Prussian Confessing Church during the Nazi regime. Hildmann was also friends with the famous hymnist Jochen Klepper (1903–1942). Klepper had married a Christian of Jewish descent and he and his family eventually took their own lives because of the Nazis’ persecution of Jews.

Hildmann had been influenced by the theology of Karl Barth (1886–1968), among others, when he had been pursuing his degree in theology. Above all, however, he had been shaped by the example set by Johann Christoph Blumhardt (1805–1880) and his son Christoph Blumhardt (1842–1919).

After his first theology exam in 1935, Hildmann first worked as a vicar in Augsburg and as religion teacher in Munich. As the personal vicar of the pastor in Starnberg, Hildmann established the Protestant congregation in Gauting near Munich on his own in February of 1936. His goal was a congregation capable of making its own decisions. He additionally introduced numerous innovations such as home bible study. Hildmann especially strove for Christian education of children and young people at school and in confirmation class. His outstanding preaching and talent for discussion also enabled him to quickly win over unchurched, educated segments of the population in and outside Gauting.

Although Hildmann had still flirted with nationalist currents during his days as a university student, during the Nazi regime, he was drawn to the “radical” Confessing Church shaped by Karl Barth. He was a member of the Bavarian Brotherhood of Pastors and repeatedly criticized the Bavarian church government’s willingness to compromise toward the Nazi state. Although Hildmann himself remained fundamentally loyal to the state, he expressed negative views about church policy and the Nazis’ claim to ideological totality more and more frequently in courses and sermons. He rarely displayed any regard for the consequences that threatened him because of his candid remarks.

Congregational members who were convinced Nazis denounced Hildmann to the Gestapo as well as to the church government several times. His teaching especially put him at risk. He had already been reported to the authorities in 1935 for making critical remarks about the NSDAP’s chief ideologue Alfred Rosenberg (1893–1946) and defending the Jews in religion class. In July of 1937, a complaint was lodged with the regional consistory because he had read the list of detained and disciplined pastors in the prayers aloud during worship service. He repeatedly had to justify his behavior to his ecclesiastical superiors but the church government protected him time and again.

After charges of violating the “Treachery Act” had been dropped before Munich Special Court in 1937, the chairwoman of the National Socialist Women’s League in Gauting file a complaint with authorities against Hildmann for pacifistic propaganda. These charges were also dropped because it could not be proven that he had said that it can never have been God’s will that people should kill each other in wars (B. Mensing, Rücksicht, 336). He was denounced yet again in May of 1938 when he, along with Pastor Kurt Frör and others, had circulated a pamphlet on Martin Niemöller’s trial and internment in a concentration camp. This time, the report to the authorities had fatal consequences for him.

A house search, detention and interrogation forced him to break off his second theology exam. The Nazi leadership especially reproached Hildmann for his statement that the present state is less concerned about law and more about power (B. Mensing, Rücksicht, 337). As a result of the proceedings, he was forbidden to hold a youth bible retreat. Above all, however, he lost his license to teach religion class in November of 1938. The church government also felt compelled to take action then. In January of 1939 a church councilman in Gauting drew the regional consistory’s attention to Hildmann’s weakened state of health and he was granted leave with immediate effect.

This leave of absence, probably also for his own protection, was extended several times, without pay, though. In March of 1939, the church government replaced Hildmann in Gauting with another vicar. Regional Bishop Hans Meiser (1881-1956) obtained a deferred sentence for Hildmann when hewas sentenced to four months of prison at the trial in June 1939. He was drafted into the Wehrmacht In August of 1939 and took part in the invasion of Poland. The charges were dropped in 1940. That same year, he received his marching orders for France where he was killed near Abbeville on May 28, 1940. His body was never found.

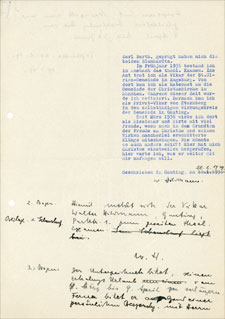

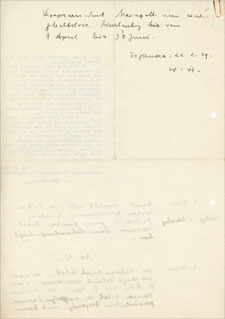

Source / title

- © 1+2: Private collection of the Hildmann family, Tutzing