Farmers: Voting against Non-denominational Schools

The Nazi leadership especially combatted the churches’ public influence in the realm of education of children and young people. To this end, they began eliminating denominational schools in Bavaria, too, and propagated the establishment of non-denominational schools throughout the region. They argued that denominational schools disturbed denominational peace and imperiled upbringing as part of the national racial community. They additionally claimed that religion class sufficiently assured the Christian character of non-denominational schools. The Bavarian church government nevertheless feared that the Nazi state intended to eliminate Christian influence in non-denominational schools and introduce Alfred Rosenberg’s weltanschauung (1893-1946) instead.

Regional Bishop Hans Meiser (1881-1956) had therefore admonished Protestant parents in a pulpit announcement of December 1933 to send their children to denominational schools and additionally pointed out the right to establish Protestant schools established in the agreement of 1924between Bavarian the church and state. The fierceness that the struggle for denominational schools would assume already began emerging one month later when the NSDAP deemed another of Meiser’s appeals on the school issue to be an act of sabotage and libel of Hitler. The struggle for denominational schools became urgent when the Nazis began pursuing the elimination of the churches’ influence in all spheres of society under the slogan of “de-confessionalization of public life” in 1935.

At first, special provisions of education laws were exploited to eliminate the denominational schools in Bavaria. These routinely required parents in cities, such as Nuremberg, Munich und Weissenburg, to vote for a type of school when they registered their children for school. State and party authorities put heavy pressure on teachers and parents before school registration and threatened and coerced them into voting for non-denominational schools. While the church did not have any means to represent its point of view in the coordinated press, the Nazis were able to bring their entire propaganda machinery to bear in order to get the populace to commit to non-denominational schools.

The church government, deans and pastors protested against the obvious breach of the law and the coercion of parents in numerous petitions to the state and party authorities. Entrusted by the church government with leading the school struggle, Helmut Kern (1892–1941) and Kurt Frör (1905–1980) particularly rose to prominence in the disputes over the denominational schools. As had happened in the fall of 1934, a delegation of laypersons from Nuremberg even traveled to Berlin in December of 1936 to protest to the Reich Ministry of Education. The Nazi leadership, however, portrayed the pressure exerted on parents as “education” of the populace, placed the blame for the school struggle on the church and declared registration for non-denominational schools to be legal.

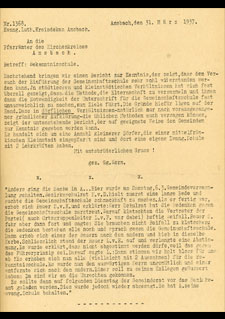

Once over ninety percent of the parents in the affected Bavarian cities had registered their children for non-denominational schools in early 1937 and the denominational schools there had been abolished, Bavarian Minister of Education Adolf Wagner (1890–1944) also began eliminating the denominational schools that still remained in the countryside. He proceeded with the same methods as in the cities before. This made the actions of some farmers all the more courageous. In March of 1937, farmers pushed through a vote at a town meeting against the will of the party representative in attendance, which was decided in favor of denominational schools. Admittedly, Minister of Education Wagner achieved his goal nevertheless: As in Württemberg before, the denominational schools in Bavaria were eliminated at the turn of 1937-38.

Source / title

- © Evangelische Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Kirchliche Zeitgeschichte München, A 30.6