Wolfgang Hammer: Against a Senseless Final Battle

Born the son of a Protestant teacher in Ansbach, Wolfgang Hammer (1926–1995) attended Carolinum High school. A close friendship bound him with his Catholic classmate Robert Limpert (1925–1945), a resistance fighter who remained controversial in Ansbach until the end of the 20th century.

Raised Christian conservative by their parents, Hammer and Limpert already shared a skeptical view of Germany’s military situation before the catastrophe of Stalingrad. Hammer and Limpert were expelled from their school in November of 1943 for eavesdropping on a teacher conference held because they had written messages critical of the war and regime on several chalkboards in the Carolinum in the night. The two were able to graduate from a high school in Erlangen in February of 1944.

Robert Limpert, who suffered from a heart condition, wanted to study Oriental languages in Switzerland. When this was denied him, he began studying theology at the university in Würzburg. Wolfgang Hammer was drafted into the Wehrmacht and, after being wounded several times at the Eastern Front, returned to Ansbach at Christmastime of 1944. With interdenominational solidarity, the friends then discussed the question of whether it was not imperative to put up resistance.

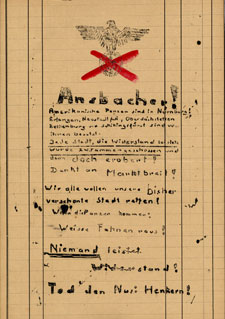

Following another deployment, Hammer returned to his hometown in earl April of 1945 and produced pamphlets with Limpert and former schoolmates Hans Stützer and Herbert Frank in which they called for the surrender of Ansbach to the advancing American troops without a fight and for Death to the Nazi Executioners!

They made copies of their texts with matrices in a government office to which they had gained entry. They posted the texts on churches, doors and walls and, especially provocatively, in NSDAP display cases for which they had gotten ahold of a key. The group distributed not only the up to two hundred copies of pamphlets but also large numbers of handbills and propaganda material that had been dropped by Allied aircraft. As a result of these actions, the party threatened to declare Ansbach to be under a state of siege.

In a spontaneous action, Limpert cut a telephone line on April 18, 1945, which he thought led to a Wehrmacht unit positioned before the city. Actually, the soldiers had already fled. Limpert was denounced and sentenced to death by the commandant of the city who brutally murdered him with his own hands a few hours before the Americans arrived. Hammer’s name was later found along with those of Limpert and others on a blacklist of political opponents, which the Nazis had compiled.

After the war, Wolfgang Hammer earned a degree in theology. He became the city vicar in Augsburg in 1953 and the director of studies at the Evangelische Akademie Tutzing in 1955. Two years later, he took on a parish in Starnberg. He then transferred to the Graubünden Evangelical Reformed Regional Church in 1957 and took on the parish in Bivio. In 1967, he became a pastor in St. Moritz.

Along with serving his parish, Hammer occupied himself with history and self-published two small books, one on the life of the Swiss reformer Ulrich Zwingli (1981) and one on the Battle of Königgrätz (1984). Above all, however, he studied Adolf Hitler in-depth.

In 1970, the university in Munich awarded him his doctorate for his dissertation on “Die historischen, kulturellen und kirchlich-theologischen Strukturen in Adolf Hitlers Jugend und Heimat. Ihre politischen Wirkungen unter seiner Regierung und seine Urteile darüber” (The Historical, Cultural and Eclesio-Theological Structures in Adolf Hitler’s Youth and Homeland. Their Political Impact under His Government and His Opinions of Them). Between 1970 and 1974, he published the three-volume “Dialog mit dem Führer” (Dialog with the führer) in which he described Hitler as a messiah, tyrant and prophet. Despite his decidedly Christian perspective and more annotative than analytical approach to Hitler, Hammer refrained from the confessional polemic still common at that time.

Source / title

- © Private collection of Alexander Biernoth, Ansbach