Hans Meiser: Warning against Deifying the State

The Evangelical Lutheran Church in Bavaria’s first bishop as of May of 1933, Hans Meiser (1881–1956) had risen steadily in the church hierarchy during the Weimar Republic. His absolute fidelity to the Lutheran Confession, exceptional diligence, great organizational talent, strong leadership and ability to compromise helped him into leadership positions in the church early on.

Having acquired a good reputation as the chaplain of the Inner Mission in Nuremberg and as a pastor in Munich, he was appointed director of the newly established theological seminary in Nuremberg in 1928 and to the high consistory of the Munich church government in 1922. At the end of the Weimar Republic, Meiser was considered to be the coming man in the regional church.

Shaped in Imperial Germany, Meiser, like the large majority of German Protestants, was unable to establish a positive relationship to religiously neutral parliamentary democracy. He continued to labor under a conception of a Christian government that held that the state was a divine order to which a Christian had to render obedience.

He viewed the end of state churchdom in 1918 as a loss but also saw great opportunities presented to the church by its newly obtained independence from the state. He formed devastating opinions of the social and cultural development in the Weimar Republic and viewed them as an utter decline.

In keeping with his understanding of his office as a pastor, involvement in partisan politics was not an option for Meiser. His opinion of political parties was chiefly based on their stances toward Christianity and church. From the outset, he therefore ruled out the left-wing parties, which he identified with godlessness, hostility toward the church and moral decline.

He tended to sympathize with the conservative and emphatically Protestant Christian Social People’s Service, an offshoot of the German National People’s Party. He maintained the partisan political neutrality demanded of pastors, however, and refrained from publicly backing any one party.

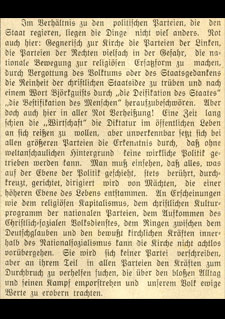

Not until Bavarian pastors actively took part in the bitter partisan political struggles in the final phase of the Weimar Republic and agitated for the Nazis did Meiser express his views on the parties as well as his opinion of National Socialism in the “Korrespondenzblatt für die evangelisch-lutherischen Geistlichen in Bayern”.

In his New Year's message “Hardship and Promise” of early 1931, he asserted that the right-wing parties are frequently in danger of making the national movement a substitute religion and are clouding the purity of the Christian concept of the state by deifying ethnic peoplehood or the conception of nationhood and are bringing about “the beastialization of human beings” by “deifying the state”.

He realized at the same time, however, that the church cannot heedlessly ignore the consciously ecclesiastical forces in National Socialism …. Although they do not commit to any one party, they are doing what they can in every party to help the forces get accepted, which are looming over mere everyday life and its struggle and striving to snatch eternal values from our nation.

Source / title

- © Evangelische Arbeitsgemeinschaft für Kirchliche Zeitgeschichte München, KK 3.4850