Church Government: Between Affirmation and Protest

While the majority of Bavarian pastors and parishes joyfully welcomed Hitler’s assumption of office on January 30, 1933, the church government under Church President Friedrich Veit (1861–1948) maintained its silence. In view of the political challenges and his disapproval of National Socialism, Veit he no longer appeared to be the man suited to lead the regional church. Under pressure from pastors with Nazi leanings and out of fear of a revolutionary seizure of power by the German Christians, Veit was ultimately urged to resign from church government bodies.

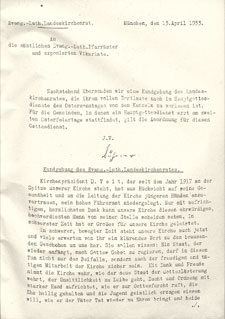

In this situation, the regional consistory issued a communiqué at Easter of 1933 in which it welcomed the Nazi state thankfully and joyfully and assured the church’s assistance. This was motivated by the hope that the new state would be based on a Christian foundation, enhance the status of the church and bring about the re-Christianization of the nation. The regional consistory completely ignored the Nazi regime’s display of its inhumane and criminal face when it had taken revenge on political opponents and boycotted Jewish businesses.

Nonetheless, out of fear of an attack on the church, the regional consistory also distanced itself in its communiqué from the Nazis’ claim to totality. It additionally declared that the church’s message would not be affected by political changes and that the church had to fulfill its mission on its own authority.

It also outlined the principal features that would become determinative for the course of the new church government elected by the regional synod on May 4, 1933: partial affirmation of the Nazi state, on the one hand, and protest against attempts to coordinate the regional church and misrepresent the confession, on the other.

The synod elected Hans Meiser (1881–1956), a member of the high consistory, new church president. Although not a Nazi himself, he was considered to be open-minded toward the new leadership. At the same time, the office of the church president was converted into the office of the regional bishop and endowed with authoritarian plenipotentiary powers modeled after the state’s Enabling Act of March 1933. This was intended to assure the regional church’s ability to act in the new political circumstances.

Meiser’s installation in office on June 11, 1933 turned into a demonstration of the good relations between state and church (C. Nicolaisen, Herrschaft, 302). This soon changed, however. The church government already saw itself repeatedly compelled in 1933-34 to protest against individual ecclesio-political actions taken by state and party authorities, most notably in the field of youth work and school.

The main battlefield, however, was the defense of the regional church against the claims to power of the German Christians, who were patronized by Hitler. They had gained ground in Bavaria in the church elections in July of 1933. Through concessions and a clever staffing policy, Meiser succeeded in getting the Bavarian German Christians to submit to his authority and thus prevented a schism of the regional church.

The Bavarian church government also took part in the national struggle against the German Christians. When it became clear in the fall of 1933 that Reich Bishop Ludwig Müller (1883–1945) intended to coordinate the church with the Nazi state, not only organizationally but also ideologically, the Bavarian regional church assumed a leading role in uniting opposition within the church in the Confessing Church.

The regional church itself became the target of the Reich Bishop’s policy of Gleichschaltung in the fall of 1934. Nevertheless, the nearly united resistance from the regional bishop, the church government, pastors and parishioners thwarted his attempt to incorporate the regional church forcibly in the Reich Church, which he had undertaken with the support of political authorities. The Bavarian regional church preserved its confessional teachings, constitution and legitimate government.

Time and again, the church government under regional bishop Meiser proved to be willing to compromise in the face of the Nazi state’s ecclesio-political expectations and demands. For instance, Meiser had voted for “the Führer’s representative”, the German Christian Ludwig Müller, in the Reich Bishop election in September of 1933 and, under pressure from Hitler, backed Müller once again in January 1934, even though his conduct was contrary to the Confessions.

The church government protested against political measures by the state and party only in a few exceptional cases. It refrained entirely from criticizing the Nazi state’s policies publicly. Partial affirmation of National Socialism and Lutheran tradition, which did not view participation in political affairs or criticism of government actions as part of the church’s mission, merged here.

Church leaders did not want to or failed to recognize National Socialism’s true nature. Like nearly all German Protestants, they additionally lacked the theological tools to grapple with the totalitarian Nazi regime’s policies.

Thus, only a few individuals in Bavaria, such as Karl-Heinz Becker, Wilhelm Freiherr von Pechmann and Karl Steinbauer, had a sharp eye for the crucial problems early on (F. W. Kantzenbach, Der Einzelne, 197). They recognized not only the fundamental irreconcilability of Christianity and Nazi ideology but also the criminal nature of the new state. They hoped for a clear statement from the church government. Their appeals went largely unheeded, though.

Source / title

- © Landeskirchliches Archiv Nürnberg, LKR XVII 1758