Protests against the “Jewish Badge”

On September 9, 1941, a police regulation forbade all Jews still residing in the German Reich to appear in public without a Jewish badge (Hermle, Thierfelder, Herausgefordert, p. 649). It was supposed to be a saucer-sized, six-pointed star made of yellow fabric bordered in black bearing the label “Jew” in black and sewn visibly and securely on the left breast of a garment.

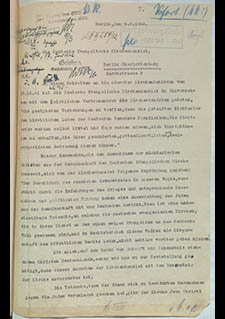

As a result, the German Evangelical Church Office, in agreement with the Religious Liaison Committee, issued a circular on December 22, 1941 to every church government, calling on them to make provisions that baptized “non-Aryans” stayed out of church life. (Ibid., p. 654).

Whereas signs prohibiting them – no Jews allowed – were posted in German Christian churches in Saxony for instance, the Conference of Councils of Brethren and the Second Provisional Church Government protested against this ostracism of baptized Jews, just as Bishop Wurm had done.

The Church Office’s request is irreconcilable with the church’s beliefs, was the Conference and the Provisional Church Government’s blunt and direct repudiation of the Church Office’s directive in a letter of February 5, 1942 (Ibid., p. 658). Pointing out that Jesus commanded baptism and that Jesus himself and all of his disciples had been Jews, they called upon the Church Office to withdraw its memorandum.

Bishop Theophil Wurm also intervened and inquired unusually harshly about the theological basis of this directive. On February 6, 1942, he provided detailed reasons for his disapproval and employed rhetorical questions to point out not only its theological problems:

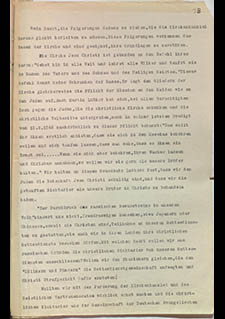

The exclusion of baptized non-Aryans cannot be justified by the Gospel. The reference to an earlier or still extant separate community speaking a foreign language does not work because non-Aryan Christians speak the same language as we.

Are the churches permitted however to heedlessly ignore the fact that Jews are being excluded from the German Volksgemeinschaft? Certainly not. A Christian may not heedlessly ignore any unfortunate person. Nobody would deny that non-Aryan Christians are the unfortunate people today. Are we permitted to increase this misfortune even more by not allowing them to attend our church services? (Schäfer, Fischer, Landesbischof, p. 155).

The Religious Liaison Committee made a not very convincing attempt to defend its directive in its reply to Wurm. It was not repealed.

Katharina Staritz, a city vicar and liaison for “Grüber’s Office” in Breslau, likewise appealed to her fellow clergy on September 2, 1941 in response to the “decree introducing the Jewish badge”. She reminded the theologians that it is congregations’ Christian duty not to exclude Christians of Jewish descent, now forced to wear the yellow star, from church services simply because of the badge. They have the same right to a home in the church as other congregation members and are especially in need of comfort from God’s Word (Hermle, Thierfelder, Herausgefordert, p. 650).

She suggested considering instructing church officials, ushers and the like in proper pastoral form to minister to these marked congregation members in particular, to show them seats when necessary and so on. Perhaps, special seats ought to be provided in every house of worship, however not as a sinners’ pew for non-Aryan Christians but rather to protect them from being turned away by unchristian elements (Ibid., p. 651).

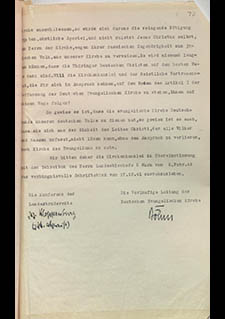

From then on, Staritz was subjected to Gestapo surveillance and the German Christian consistory also aligned itself against her. After an interrogation on October 21, 1941, Staritz was dismissed. She found refuge in Marburg.

Following a smear campaign conducted against her in the SS weekly “Das Schwarze Korps”– “Miss Smartweed as City Vicar” – she was arrested on March 4, 1942 and interned in Ravensbrück concentration camp in May. She was released unexpectedly on May 18, 1943. Back in Breslau, she had to report to the authorities twice a week and was no longer permitted to make public appearances.

Source / title

- © Evangelisches Zentralarchiv in Berlin, Bestand 1 No. 3073